|

This is a passage taken

from an academic paper written within a Humanities

framework. |

|

This is a passage taken

from an academic paper written within a Humanities

framework. |

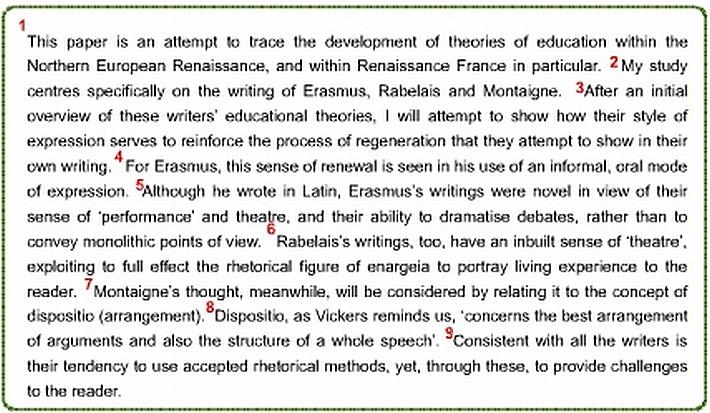

1. This is the first sentence of the passage and introduces the paper. No discourse markers are necessary. Note that the author expresses an Anglo mentality in that s/he BEGINS by stating her/his PURPOSE (what the paper proposes to demonstrate). It would have been better if the author had also indicated her/his CONCLUSIONS . For example, s/he could have written: “This paper is an attempt to trace the development of theories of education within the Northern European Renaissance, and within Renaissance France in particular. It will show a increasing emphasis placed on the learners (or readers) of a text, made to “live” that text. My study centres...

2. “Specifically” is a marker that says that sentence 2. indicates the “focal point” or “specific point” that will be discussed in the paper. To be even more explicit, the author could have put a marker at the beginning of the sentence: “In particular...” (eliminating “specifically”).

Now that the author has told us where s/he wants to take us (sentences 1 and 2), s/he tells us in sentence 3 how her/his paper is structured (in other words, how she plans to take us there).

3. This sentence outlines the sequence of events in the paper. “After” is used in the first clause to indicate not time (as in “after lunch”) but sequence: “After I explain A, I will explain B; and after B, C.” By telling us how s/he plans to lead us to her/his CONCLUSIONS, the author is giving us a complete picture of her/her paper. In addition, she is making explicit her/his communicative intent: “Dear reader, I want you to believe A, then B and finally C, which will lead you to my CONCLUSION.”

4. The marker “For... “ (or “As for...”) plus “Erasmus” marks the first step described in sentence 3. The author could have simply written “As for the first case, the sense of renewal...” but “As for Erasmus” (or simply, “For Erasmus”) is clearer because it is more specific. The following word, “this” acts as a marker, too: it links the present sentence with the theme (“regeneration”) announced in the previous sentence. When the author writes “this sense of renewal”, s/he does not mean ANY sense, s/he means the sense of renewal that was just mentioned: the “regeneration” of a view of education and of writing. We call the use of “this” in sentence 4 an “anaphoric reference” ( a word that refers back to something already said). To conclude, “this” is not an official marker word, but acts as an anaphoric marker in this sentence.

5. This sentence gives us more information about Erasmus, information that indicates a concession, marked by the official discourse marker “although.” The author concedes that Erasmus wrote in Latin, which should logically mean that Erasmus wrote very formally. But in spite of this, the author tells us that Erasmus did not write formally, but rather in a very lively way, by expressing his ideas through dialogues. When you read them, you feel you are hearing a theatre production. The marker “although” is thus used to express the concept “but in spite of”.

6. The author could have begun this sentence with

“For Rablais...” (just as s/he began sentence 3.

with “For Erasmus...” but too much explicit

parallelism can be monotonous. The author probably thought that by

beginning the sentence just with “Rablais”, the

reader would remember sentence 2 (“we will speak of

Erasmus, Rablais and Montaine”) and therefore understand

that the present sentence constitutes the second step in her/his

3-part demonstration. “Rablais” is therefore an

anaphoric reference to itself in sentence 2.

The word “too”

is also an anaphoric reference: it refers back to the concept

expressed in sentence 5, the concept of (theatrical) performance.

This maker makes it clear that the points discussed so far (Erasmus,

Rablais) have something in common, which is leading us toward the

final CONCLUSION. They have in common a

way of writing that then became a way of teaching: a way that was

lively, based on representations that draw the reader or learner

into the action.

7. Just as in sentence 6, the author begins with the name of the writer, and not “For... [+ the name of the writer],” to avoid being monotonous. Here, just the word “Montaigne” reminds us that this sentence represents the third step in the demonstration: 1-Erasmus, 2-Rablais, 3-Montaigne. The author uses the marker “meanwhile” to show that Montaigne is a continuation of his argument but, at the same time, does something different. (Montaigne continues the new tendency toward lively writing but, instead of using dialogues or narrations, he draws his readers into his text by the way he organizes the different parts of the text.) Dispositio is the Latin word for Organization or Disposition or Arrangement of the parts of a text.

8. This sentence is linked with the previous

sentence by means of the repetition of the word “Dispositio”.

As we said when speaking of sentence 4, simple repetition is a very

explicit way to mark a connection, but it can also appear

unimaginative and boring. Here the author could have been less

explicit but more interesting by using a non-repetitive anaphoric

reference like: This procedure...” or “This

rhetorical device...”

So, in conclusion, how

explicit should you be? If you are very explicit, everyone

understands you but you can appear simplistic. If you are not very

explicit, you can seem interesting but only to those who understand

you. The art of writing is to imagine your future public (the people

who will read you), imagine their capacity of understanding ideas

that are said less and less explicitly, and then choose the level of

explicitness that is best for them.

9. In this sentence, the author concludes this passage by saying what is common to all three writers (their respect for the rules of traditional writing) and what distinguishes them from other contemporary writers (their innovative use of language to “draw the reader into the text”). Since these two ideas are in opposition, the author links them with a concessive marker “yet.” (“Yet” as a temporal marker means “until now” or “already”; as a concessive marker it means “in spite of”.)

The author has not yet reached his final conclusion: he has not yet shown that the three authors also propose educational methods that “draw the students into the learning process.” But he is now ready to formulate explicitly his PRELIMINARY CONCLUSION: during the Renaissance and in particular in France, a new way of considering the reader of a text was beginning to appear. Instead of precepts, Erasmus, Rablais and Montaigne offer their readers participation.

|

The above “passage

taken from an academic paper” was prepared by Gerard

Sharpling of CELTE; |